In today’s episode we hear from Gregg McNeill of Darkbox Images, discussing the tangibility of analogue processes and why wet plate collodion (a Victorian photographic technology) endures to this day.

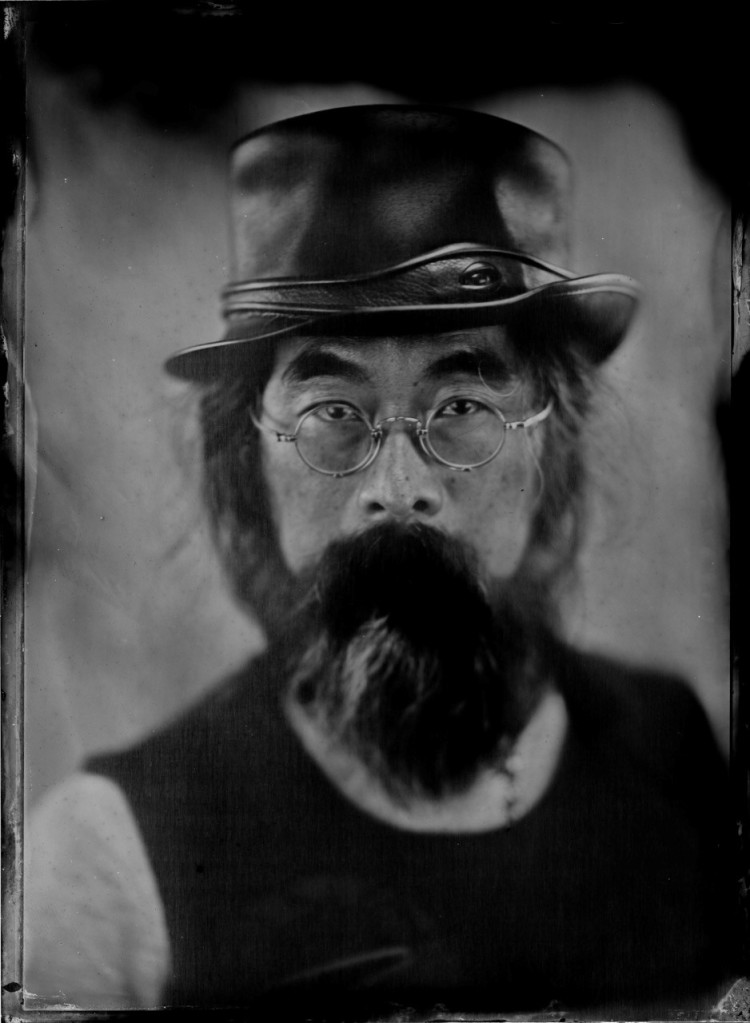

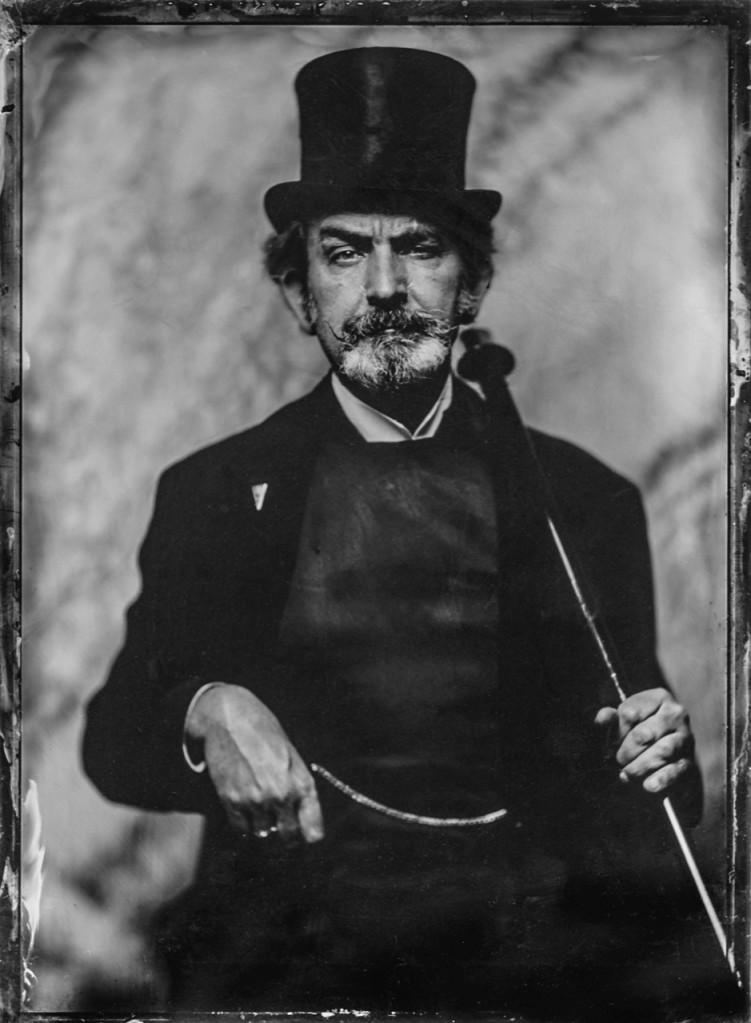

Gregg lives and works in Larbert as a photographer and film-maker, employing both digital and analogue photographic processes (examples of collodion work below) to create beautiful and unique images. We are fortunate enough to be hosting Gregg at HippFest 2024, where we know our audiences will savour the opportunity to sit for a unique portrait to take home.

Excitingly, Gregg is offering a special perk for Festival Pass Holders, who will receive a complimentary debossed cabinet card to display their portrait in style!

In conversation with Digital Content Manager (and podcast wrangler) Christina – who incidentally, is also an analogue photographer – Gregg discusses the fundamentally physical process of shooting 16mm film, how lens-based technology has affected how we see and tell stories, the beauty of the collodion process, and the value of physical photographic ephemera.

We hope you enjoy the episode and have a restful break. Relevant links below!

See examples of Gregg’s wet plate collodion work below…

Various relevant links

- Gregg’s Patreon account: https://www.patreon.com/DarkboxImages

- Darkbox Images: https://www.darkboximages.com/

- Book a HippFest 2024 Festival Pass: https://www.hippodromecinema.co.uk/ticket-subscription/

- More on Frederick Scott Archer, inventor of the collodion process: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_Scott_Archer

Show transcript

Alison Strauss: Hello everyone and thank you for tuning in to HippCast Episode 10. This time last year we were releasing our first ever primer episode and tentatively beginning our podcast journey. Thank you for joining us along the way. I hope that as the festive season approaches you’re finding time for moments to enjoy your favourite things, whatever they may be.

Alison Strauss: I’m looking forward to switching off and catching up with a pile of books by my bed and eating party food. In the meantime. Here at HippFest HQ, we have exciting news… we have released our 2024 HippFest Festival passes for sale just in time for Christmas! Our 2024 Pass offers new discounts and local offers, plus 15% off in the Hippodrome Cafe and Bar. The standard Festival Pass costs £145, or you can upgrade to be a Festival Supporter at £175.

Alison Strauss: All Pass Holders will be able to access priority booking and take their pick from all the screenings and the talks at the Hippodrome and the Barony Theatre in Bo’ness with no booking fees, plus automatic registration to all HippFest at Home online events in the run up to the festival. Supporter Pass Holders will be thanked with an on screen credit and receive a wee minding, as they say here in Scotland, a wee present, wee treat and surprise perks. We really are delighted to be able to offer the convenience of a pass, and we hope you find it an attractive option. And as you may know, we rely on grants and sponsorship for more than 80 percent of HippFest costs, and so we’re asking if people will consider purchasing the Festival Supporter Pass if they feel able to do so.

Alison Strauss: We invest all of the box office income we make back into the festival so that we can continue to bring great films with live music, engagement, and much more to a wide audience. And those who can pay more help us to do this whilst keeping the lowest price tickets really affordable for others. Just to say the festival passes are limited and subject to availability, so bag yours early to be sure you don’t miss out.

Alison Strauss: We are delighted also to share the news with you that we will be welcoming Gregg McNeill of Dark Box Images to Bo’ness to capture our audiences in true Victorian style using the beautiful, unique, and inimitable wet plate collodion process. Passholders who book themselves in to sit for one of these special portrait sessions with Gregg while at HippFest will receive a complimentary debossed cabinet card to be used to present their portrait in style.

Alison Strauss: Now, wet plate collodion is an analogue photographic process which involves exposing an image onto a glass or tin plate and always involves a degree of luck and unpredictability. The technique was invented by Frederick Scott Archer in 1851, and predated silent cinema before coexisting briefly at the turn of the century.

Alison Strauss: Each collodion portrait is utterly unique, a one of a kind memento to take away and treasure. In today’s episode, our Digital Content Manager Christina, also a photographer incidentally, speaks to Gregg about his fascination with Victorian processes, his previous work on 16 mil film, and why Hipponauts should expect to fall in love with tintypes at HippFest 2024. Gregg McNeill, founder of Dark Box Images, is a wet plate collodion photographer living in Falkirk and has worked as a film and digital photographer for over 30 years. Greg’s passion for photography was reawakened after discovering the 150 year old wet plate collodion process about 10 years ago.

Alison Strauss: Now Greg’s skill in using an authentic Victorian camera coupled with his experience and precision timing creates remarkable results appear right before your eyes. He also has a passion for many other Victorian era processes including salt printing, albumen printing, and cyanotype, and these and other photographic adventures are documented online at at http://www.patreon.com/darkboximages and you’ll be able to find links to this and the Dark Box website in the episode show notes along with more details about the HippFest 2024 Festival Pass. Gregg is currently teaching wet plate collodion workshops at his studio in Larbert and we really can’t wait to welcome him to HippFest 2024.

Alison Strauss: Thanks so much to Gregg for taking the time to be part of this episode. That’s all from me now. Enjoy the show, take care, and when the time comes, enjoy a lovely winter break.

Gregg McNeill: Hello. My name is Gregg McNeil. I’m a photographer and I specialize in Victorian era photographic processes. I’m also a filmmaker. And a storyteller, and, um, basically I’ve made image-making my entire life.

Christina Webber: I didn’t know you were a filmmaker as well.

Gregg McNeill: Yeah, yeah, a lot of that was, uh, from a previous life. But I started out around the age of 13 with the Pentax K1000 and I took some photography classes at my, uh, high school, my junior high school. And then I took, continued that.

Gregg McNeill: And it wasn’t until I got to university that I started getting into filmmaking. And then all throughout that I was still using photography as a method of self expression. And, with the filmmaking thing, I, I shot some documentaries, a couple of feature films. I did a lot of corporate work. And, uh, back then a lot of our corporate work was still on 16mm film.

Gregg McNeill: So, I was always into motion pictures and capturing that way. And, uh, I pursued the filmmaking endeavors as a career. I started out as a motion picture camera assistant. So I was loading magazines and setting up cameras and pulling focus and all that sort of thing. And then I moved into, uh, DOP, Director of Photography.

Gregg McNeill: And then as, as I progressed, I started realising that the work I was doing wasn’t as fulfilling as it used to be. I got into some business relationships with some clients that were not good for me. And I just started getting really kind of bored with it. And I’m one of these people, I’m broken in a very specific way:

Gregg McNeill: if I’m not truly invested in a project, I don’t do it well. And I found with most projects, you need three things to make it successful. You need a budget. You need a deadline. And most crucially, you need someone on the other end who is as invested as you are in the quality of the outcome. And what I found was that a lot of the clients that I was dealing with, that third thing, they didn’t care about.

Gregg McNeill: They just wanted content. And, you know, you come to someone and say, the budget for this project is X. And they say, I can only give you X minus 10. And I’m broken in a way that I’m like, well, I can’t really give you X minus 10, so I guess I’m just going to give you the whole thing and take it. And, uh, I got to a point where I was just not I was not invested anymore, and my partner wanted me to find something to be interested in again.

Gregg McNeill: And so I was going through some images on Flickr, which for the young people out there is a photographic sharing platform used by old people.

Christina Webber: And Falkirk Council.

Gregg McNeill: And Falkirk Council, exactly. So, I was on Flickr looking through some images that I had liked, and I found that I had liked all of the portrait work of this one particular photographer.

Gregg McNeill: And as I looked through it, it all was the same process, and I realised oh, this is called wet plate collodion. So this is very interesting. So I looked around for workshops, and then what I found was that everybody that was teaching, currently, had been taught by one guy. And that guy was this photographer in Manchester, and I went and took his class.

Gregg McNeill: His name is John Brewer. And so, that started this rabbit hole that I haven’t found the bottom of. And one of the most interesting things about the wet plate collodion aesthetic that I loved was that this is what I had been trying to do with my photographs since the very beginning. Anything I could do to degrade the image in camera or in the darkroom, I wanted to do.

Gregg McNeill: So I was using older lenses, uh, broken lenses and printing through like broken glass and all of this other stuff just to mess with the image. And in fact, one of my good friends said to me, I was struggling with my artist statement for my first show. And what he said was, you know, what your problem is, is that you want to put as many barriers between yourself and an image as possible.

Gregg McNeill: Like you’re exactly right. That was the basis of my first artist statement. And the way that this process sees the world and the way that it renders images is the way that I see my work and have seen my work from the beginning. So I spent a lot of time photographing through plastic cameras like the Holga.

Gregg McNeill: I shot for about 10 years exclusively with the Holga. I had a bag full of four Holgas, and that was all I shot with. And that really informed the technique that I liked, and you know the vignetted edge and then when I was printing I had a hand-cut negative carrier so I got these grindy edges and it was all like using those grindy edges as part of the image frame and you got frame within a frame within a frame kind of stuff.

Gregg McNeill: I’m a sucker for that. Then going back to my first university level photography course, the teacher whose name I, has been lost to the sands of time in my memory. The first thing she did was the first day, she’s like, okay, here’s some mount board. Here’s a, here’s a template. You’re going to cut out a negative carrier.

Gregg McNeill: And we’re like, yeah, but that’s not going to be perfect. She’s like, I know. The reason I want you to do this is so that when you’re printing. If I don’t see the grindy edge of your negative carrier, I will know that you cropped in post, and you will do none of that in this class. You will be, you will fail.

Gregg McNeill: And, so every time you submitted an image, it had to have that grindy edge, and you had to submit the contact sheet with it. And, basically what she was trying to do was to get us to think about the final image while we were shooting it. And to frame in camera, and compose in camera, and not allow the crutch of printing in the darkroom to do that.

Gregg McNeill: And that aesthetic stayed with me forever. Even when I was doing digital photography, I was always composing in frame, and very rarely would I crop in post. Just because that was, you know, hammered into my head. All of these things, the grindy edges and the plastic cameras and doing pinhole work and making cameras and making lenses.

Gregg McNeill: All of that was in service of trying to get these images that I realised I could do with this one process. And I immediately, you know, you take a tintype class. And then you spend the next year and a half making really crappy tintypes until you figure out your process. You have to get that out of your system. I mean, it’s even with, uh, when I’m shooting out in the world, you know, you come to a space that you’re going to photograph and you burn the first half of your roll just on: okay, this is what everybody’s going to take.

Gregg McNeill: I’m going to get that out of my system. And it’s always the last four images on a roll that are the best because then you’ve worked your way through all of the pedestrian images and you’ve gotten to the real meat of what you’re there to shoot. And oftentimes, I don’t realize what I’m there to shoot until those last four images.

Gregg McNeill: And then you’re like, Ooh, yeah. Or the last image as you’re leaving a space. And you go, Oh, that’s interesting. Click. That’ll be the best one.

Christina Webber: Hearing you talk about your, your journey to finding wet collodion… it seems like from the beginning you were interested in the kind of materiality of photographs, even when they were digital. And I think that’s something that… when you’ve never seen a silent film before and you’ve only been to the cinema, you know, like I had, and seen films digital, modern films your whole life and then when you start watching silent cinema what really struck me initially was how much stuff there was in the print, you know? Seeing those little bits of damage, or those little bits of dust, or those little discolorations and you suddenly realize that what you’re looking at, even if it is a scan of, even if you’re not watching it actually projected from, from the, the reels, but you really get a sense of the physicality of the film as a thing. Um, cause of all those incredible little bits and discolorations and I know that we’re not, that people painstakingly work to remove them from um, restorations.

Christina Webber: But I love seeing those bits. That’s now what I love coming to silent film as an adult. Is that, that, because I love that about photography as well. The tangible object of negatives, prints, photographs, albums, you know, things with fingerprints on them. And I had never equated that as being within the film world.

Christina Webber: Because, you know, it was brought up in a time when it was just things like Pixar and, you know? Um, so I think it’s super interesting that in your, in your career, you’ve worked with both. And also I’m fascinated that when you started out in the film industry everything was still shot on 16 mil.

Gregg McNeill: Yeah.

Christina Webber: That blows my mind!

Gregg McNeill: Well, it had the best fidelity and the best resolution. Because this is before digital video. This was when the only video cameras you could get were, you know Beta cam like news gathering type things and then you got into DV cam and other things but they were still standard definition and if you wanted the best image possible you were shooting film.

Gregg McNeill: And, many of the cameramen that I worked with, we were shooting on Atons and Arri SRs and then when we were doing the bigger shows, the bigger, um, the bigger projects, we were working with big 35mm Arri cameras and yeah, it’s a… I’m a bit of a … I don’t want to say purist because that sounds a bit elitist, but there’s, there’s a texture and a language to film that is not present in digital cinema.

Gregg McNeill: And digital cinema, it’s great for what it does because it provides the perfect vehicle to get the exact vision from a director to a screen. Whereas, take silent films, for example, there’s a specific language that you can communicate with and your idea, no matter how vast it is, has to be distilled into a language that the film can read, right?

Gregg McNeill: So like, um, Méliès’ Journey to the Moon. He couldn’t create a cannon so large that he could shoot, you know, a rocket ship, right? And so he had to use his theatrical background to say, okay, well, how do I do that here? And once you get past the dawn of cinema, then you get really super creative directors who are pushing the envelope.

Gregg McNeill: And you’re starting to see, you’re starting to see cameras that are more mobile, that can move, and that can do dynamic shots. And then you have what many people considered a crutch, which was sound. Now all of a sudden the cameras were in huge, um, metal refrigerator boxes, and the microphones were huge, large microphones that had to be hidden somewhere. And people had to be in perfect position and projecting towards that. And the language of cinema had to change. All of a sudden, images were locked. Or, they would have crane shots, but it would all be, um, uh, audio that was generated after the fact. And this mobile, agile form of cinema. Stopped.

Gregg McNeill: And it really wasn’t until the sixties that you started to get that back. I mean, you had the, auteurs in the, in, in France who were doing these MOS silent style films that then would all be dubbed after the fact. Great, fine. But it wasn’t until the sixties that you got cameras that were light enough and quiet enough that you could do these things, like, um, there’s a, uh, Spielberg film. He used the first compact Panaflex camera, and he could sit in the back of this car. It was a chase film. And he wanted a camera that could record sound. And he could be in the back seat, shooting everything, real time.

Gregg McNeill: And I think that as the technology changed, so did the language of cinema change. And I think it’s like when you go to a Shakespeare play, the first ten minutes is getting your ears attenuated to the speech and your eyes attenuated to the language of what you’re seeing, right? It’s the same with a silent film.

Gregg McNeill: You’re looking at a new language and you’re having to figure out, oh, okay, so… what they’re saying and what are on the cards are different. The cards are just there to summarise. And it’s, that’s one of the things I find so fascinating about cinema.

Christina Webber: I guess it’s only when you really think about it like that that you realise how tied to processes these kinds of art forms are. Or at least how driven by processes, not necessarily tied.

Christina Webber: Which is why I think it’s interesting now, you know, 2023, that you are still practicing a photographic process from what, almost 200 years ago?

Gregg McNeill: Uh, it was invented in 1850.

Christina Webber: Okay, yeah, so over 150 years ago.

Gregg McNeill: Yeah, well over, yeah.

Christina Webber: Um, and still choosing to employ that. I mean, so first of all, for our listening audiences that have never heard of wet plate collodion photography, Would you be able to briefly explain what the process is and what it looks like?

Gregg McNeill: So, the wet collodion process is as follows. You take a plate, either glass or metal, and you coat it with a substance called collodion. Collodion is a nitrocellulose gun cotton dissolved in alcohol and ether and a couple of other things. And it’s this goopy substance, syrupy substance. And you coat a plate with that.

Gregg McNeill: You soak that plate in silver nitrate. Then, before, once that plate comes out of the silver nitrate, everything else has to be done before the plate dries. So you have to load it, expose it, develop it by hand, rinse it, fix it, and then you can rinse it again. And all that has to be done within around, I think the most I’ve been able to push it is about six or seven minutes.

Christina Webber: Wow.

Gregg McNeill: So you have to. You have your dark room there, and it has to be all done before it dries. And this process poses any number of technical challenges. First of all, it’s only sensitive to ultraviolet light, so it’s orthochromatic, much like all of the film stock up until, in some instances, the 40s and 50s.

Gregg McNeill: Um, so it only sees the blue end of the spectrum. Everything affects the wet collodion process. So ambient temperature, humidity, barometric pressure, the age of your collodion versus the age of your developer. So as collodion ages, it gains contrast and loses speed. And as developer ages, It gains contrast and loses speed.

Gregg McNeill: So, you want to mix your collodion and your developer at the same time so you can roughly hope for some kind of, um, consistency. And that’s one of the things that intrigues me about it is that every single image that you make, it’s, it’s, it’s unique. It’s one of a kind every time. You can have the same exposure time, the same everything, and the images will be slightly different.

Christina Webber: I mean, it’s interesting, I think, in a society driven by convenience, or at least as it appears in a kind of in a in a scientific or a in a technological progress timeline driven by convenience and making everything more and more convenient and you know now we have cameras in our phones, and you can take a picture so easily.

Christina Webber: What is it about that process, that process, which, I know you’ve described how the aesthetic is what you were already trying to create and I can appreciate that it must be very magical. But what is it about that process that so much is, is limited and you know, and so much is restricted and you’re, you’re trying to do a lot within that six, seven minutes.

Christina Webber: What is it that you fell in love with about that as opposed to more convenient forms of photography?

Gregg McNeill: Well, first of all, this is probably, it’s the second most inconvenient form of photography we’ve ever created as humans. But what I love about it is that you, you are a part, as you create the image, you are a part of the image creation in a very physical way.

Gregg McNeill: You pour the collodion onto the plate, so everything you do affects the image there, right? You place the image into the silver nitrate, and if you do that wrong, it can all go. Every, every step of the way you influence the look of this image, and I’ve created the image by hand every single step of the way.

Gregg McNeill: There is very little you can do after the image is developed to change it. I mean, there’s no Photoshop. There’s one thing you can do if the image is a little bit overexposed. You can use a farmer’s reducer and maybe bring it down a little bit, but I have to say it rarely works out well. But it’s, it’s the visceral involvement in every step of this handmade image that fascinates me.

Gregg McNeill: And even when I was shooting film, there’s still a part of that that I have no part of, right? You know, the emulsion’s gonna do what the emulsion’s gonna do, but I gotta say modern emulsions are incredibly forgiving. I mean, two stops either way, you’re, you’re fine. Back in the day when you were shooting ektachrome it was like you have a half a stop over and a half a stop under.

Gregg McNeill: And if you didn’t nail your exposure perfectly, the image was it’s nothing. It’s crap. Which makes me have so much respect for the National Geographic photographers. That’s all they shot. Ektachrome. And they would go out into these harsh environments and come back with images that were just bang on perfect.

Gregg McNeill: And that, as a technician, that is amazing. With this process you have to be able to accept and embrace the imperfections that the process gives you. Um, the, the grindy edges of the image from the plate holder. And the interaction of the silver nitrate and your plate holder. You can do a lot to mitigate that, but you have to accept that it’s going to be there.

Gregg McNeill: You’re going to see minute ridges of the collodion as it’s poured off the plate. It creates these tiny ridge lines. And you will see them if you go in and in and in and in and in. This is not a format for pixel peepers. You know?

Christina Webber: Not phrase I’ve heard before.

Gregg McNeill: Well, it’s like, it’s like when you, when you, um, take a digital photograph and you blow it up to 300% in Photoshop to see if it’s sharp. If it’s not sharp at 300%, it’s crap. Which… I, I think focus is kind of overrated. But this, this type of photography really forces you to… Well, it’s hard to explain. You have to think of the image in a different way. It’s not going to be perfect. And I know there are wet collodion photographers out there who are far better than I am.

Gregg McNeill: I am I would not consider myself I’m not a master of this, of this type of photography. I would consider myself an experienced novice, really. I’ve only been doing it since 2014. And there are people out there that are making images of a much higher caliber than I am. I tend to be really process driven and process oriented.

Gregg McNeill: And so I approach my work from a process avenue versus a thematic or a subject way that most photographers do. I want to see what this process can do and then I want to use what that process can do to make something interesting.

Gregg McNeill: And this goes back to motion pictures, where it is a physical medium. You are physically taking the film and loading the film into the camera. The camera is physically moving the film through the gate and exposing each individual frame.

Gregg McNeill: And there’s something that I find highly comforting about the sound of a cinema camera as it’s shooting. Um, like the sound of an Aton XTR, and Aton is a French camera, it’s the quietest, steadiest film camera ever created. And the sound of it is this little, And versus like the, the Arri 2C, which is a 35 millimeter.

Gregg McNeill: M. O. S. camera, so it doesn’t have a blimp, and it sounds like a sewing machine. And, you have these old hand cranked cameras, and they have a specific sound to them. And, the technology of those is so intriguing. When you open a hand cranked camera up from that period, you look at it, and that’s, all of those gears and cranks are handmade.

Gregg McNeill: And, at the start, it was just literally a crank attached to the gear that would move everything, right? And as that technology progressed, you got what was called the drunken screw movement, which was this chain, and the chain had a little bit of slack in it. And what the slack did was even out the downstroke versus the upstroke.

Gregg McNeill: The downstroke was always faster than the upstroke, and so the movement would be a little bit off, right? Well, this drunken screw movement allowed that to be a little more steady. And, I’ve shot with hand cranked cinema cameras before, and it’s a completely different aesthetic and a completely different way of thinking.

Gregg McNeill: If you’ve ever been on a set, you’ll hear the assistant director say, roll sound, and the sound guy will say, speed. And that’s because the old reel to reel recorders, when you would start them, they would start slow and get up to speed. And then you’d say, Roll camera and then you’d hear speed that was because the guy would have to get up to speed and all these cameramen would have different tricks to keep a steady speed and a lot of them would put songs in their head like Camptown races: Camptown races sing this song doo dah, doo dah… And that was how they kept proper speed.

Christina Webber: I thought that would drive you a bit insane after a while.

Gregg McNeill: Absolutely.

Christina Webber: Consistently singing that in your head….

Gregg McNeill: But the other thing with that is that, at that time, you couldn’t look through the lens of your camera. You had, you had what were called parallax finders. And you could kind of see, almost. But basically you were just pointing it in the direction.

Gregg McNeill: And it was lots of wide shots, and then for the close ups, you would carefully measure out the distance. Yeah, it’s really, it’s a different way of working and it’s a slower way of working.

Christina Webber: I think it’s very easy to forget the physical, the physicality of shooting, of using all of that equipment.

Gregg McNeill: Yeah.

Christina Webber: And equally, as you were saying earlier about the wet plate collodion images that you produce and about how… there’s not really much you can do to them afterwards, because it all has to be right during that six, seven minutes. But I think what’s really unusual today is, and correct me if I’m wrong, but with wet plate, with tintypes and, the images that you produce, there is one thing, you know, there is one thing produced.

Christina Webber: And that’s it, you know, it’s one unique… and I think even with prints and stuff, it’s really unusual to a lot of people to think about a solid photograph, you know, a piece of glass or a piece of metal, that is, that is the object. That, to me, is really special, and I think… because we’re so not used to handling photography – I mean we probably are because we’re weird and we like analogue photography – but most people aren’t used to having this one super precious, one thing, you know, one image.

Gregg McNeill: It’s like Victorian Polaroid really. Yeah, it’s one of one. And, the people who recognize that it’s something precious and special, that’s really who my audience is. And like, when I go through this process and make a portrait with somebody, the way I do this is that I… the sitter is part of the story. And we make this image together, so they’re there and looking at each individual step in this process. It takes around 15 minutes.

Gregg McNeill: So I talk to them as I’m pouring the collodion, saying this is what we’re doing here, this is going here, and I explain a little bit about the history of the process and its effects on Victorian society. And then we sit for the photograph and they sit there for between four and seven seconds in a head brace. And then after that, they go to the darkroom, and I usually have a little monitor set up with a live video feed to the darkroom so they can see the development of the image and see the image coming up.

Gregg McNeill: And then we go to the fixer and the fixer is what I call the magic bit. That’s where you watch the image turn from negative to positive right before your eyes. And that’s the… that’s the magic. That’s the real great part. And then And then it gets rinsed and dried and mounted and when, invariably, when I hand it over to someone, they take it with both hands and kind of have this moment of either, what the hell am I going to do with this now?

Gregg McNeill: Or wow, this is something really special. And I think it’s that kind of physicality that we have, this connection with our photographs. That has kind of been lost if they’re only on a screen. Even if they’re only in a digital frame. The physicality is gone. There are generations of people that have grown up without the shoebox under the bed of family photographs, right?

Gregg McNeill: My mother was very, um, was, was very particular about not having a shoebox of photographs. They were all in albums. They were very organized. Whereas other people I know, it’s just literally a shoebox and it’s just chaos. And I have to say that I have a box of photographs. They aren’t in albums. But it’s, it’s those physical things, looking at them and feeling them and touching them, especially when they’re really, really old images, like the little square black and white photographs with the scalloped edges.

Gregg McNeill: And if you’re, if you’re lucky enough to have some of the very first snapshot photographs, which are little tiny squares with circular images in them from the first Kodak camera. These, these physical objects that we have of our history are really, really important. So many of, especially our silent film history is gone, you know, through, through some through fault of our own, but you know, nitrate stock turns to vinegar and explodes and you know, there’s nothing you can do about that.

Gregg McNeill: But film preservation is so, so important as well as photographic preservation, incredibly important. And I bang this drum all the time, but in 50 or 100 years, there’s going to be a black spot in our ephemeral history, where nothing exists. At some point, no computer is going to be able to read a JPEG. And every time you back up your digital files, you’re going to lose something, invariably.

Gregg McNeill: And A lot of prominent photographers that do digital work are making physical negatives of their work for backup. Because you can always find a light source to look through something, right?

Christina Webber: It’s fascinating. Yeah, it’s kind of terrifying. At the same time, thinking about that lack of…

Gregg McNeill: Print your photographs, guys. Print your work.

Christina Webber: Or, come and sit for a beautiful portrait.

Gregg McNeill: Absolutely.

Christina Webber: And take something away with you that you can hold, and put on a mantelpiece,

Christina Webber: and pass to someone, you know?

Gregg McNeill: Exactly. We have thousands and thousands of tin types from the 1850s still with us today. It’s one of the longest lasting, hardest wearing types of photography we’ve ever created as humans. It’s resolution, still, to this day, is not matched because there is no grain.

Christina Webber: They are gorgeous. It’s like they’re made out of water. I don’t know how to

Christina Webber: describe it.

Gregg McNeill: A properly exposed and focused tintype, theoretically has detail down to the molecular level. There is no point where the grain breaks. It’s, and that’s why this process was used through the 1960s in the printing industry because there was no way to get greater fidelity for an enlargement than wet collodion.

Christina Webber: That’s amazing. Thank you so much, Gregg. I think that’s probably all we’ve got time for, although I want to continue talking about wet plate collodion for another, for another half an hour, but thank you so much. And it’s, we’re so excited to host you at HippFest 2024 and to be able to offer such a special service for our audiences, which we know will absolutely love this opportunity.

Gregg McNeill: Excellent.

Christina Webber: Thank you so much.

Gregg McNeill: Thank you.

Christina Webber: Thank you, and we’ll see you soon.

Alison Strauss: Listen out for more episodes, like and subscribe wherever you are listening. We would love it if you would rate and review this podcast to help us reach a bigger and broader audience.

Alison Strauss: A final request. HippFest needs help, and you might be our missing link. We rely on grants and sponsorship for more than 80% of HippFest costs to bring you great films with live music and much more. Could you or someone you know benefit from a sponsorship slot in this very podcast? If so, then please get in touch by emailing hippfest@falkirk.gov.uk.

Alison Strauss: We’d love to hear from you. Thank you so much.

2 responses to “HippCast: Episode 10”

Thanks for this opportunity! I had a great time making this podcast and look forward to making tintype portraits at Hippfest 2024!

I’d also like to correct something I said about National Geographic Photographers. They exclusively used a film called Kodachrome. it was a slide film, akin to Ecktachrome, but very different in its chemical composition and development. Kodachrome was made up of coloured layers of emulsion and developed using a proprietary process called K14. When you look at a Kodachrome slide in raking light you can actually see the coloured layers of the different coloured emulsions that create the image strata. Kodachrome film has unparalleled colour representation and saturation as well as incredible sharpness and fidelity.

LikeLike

Thank YOU so much for all your incredible knowledge! And thanks too for the correction – though thus far nobody else had spotted it. Now we’ll have to work Kodachrome (Paul Simon) out of our heads…

LikeLike