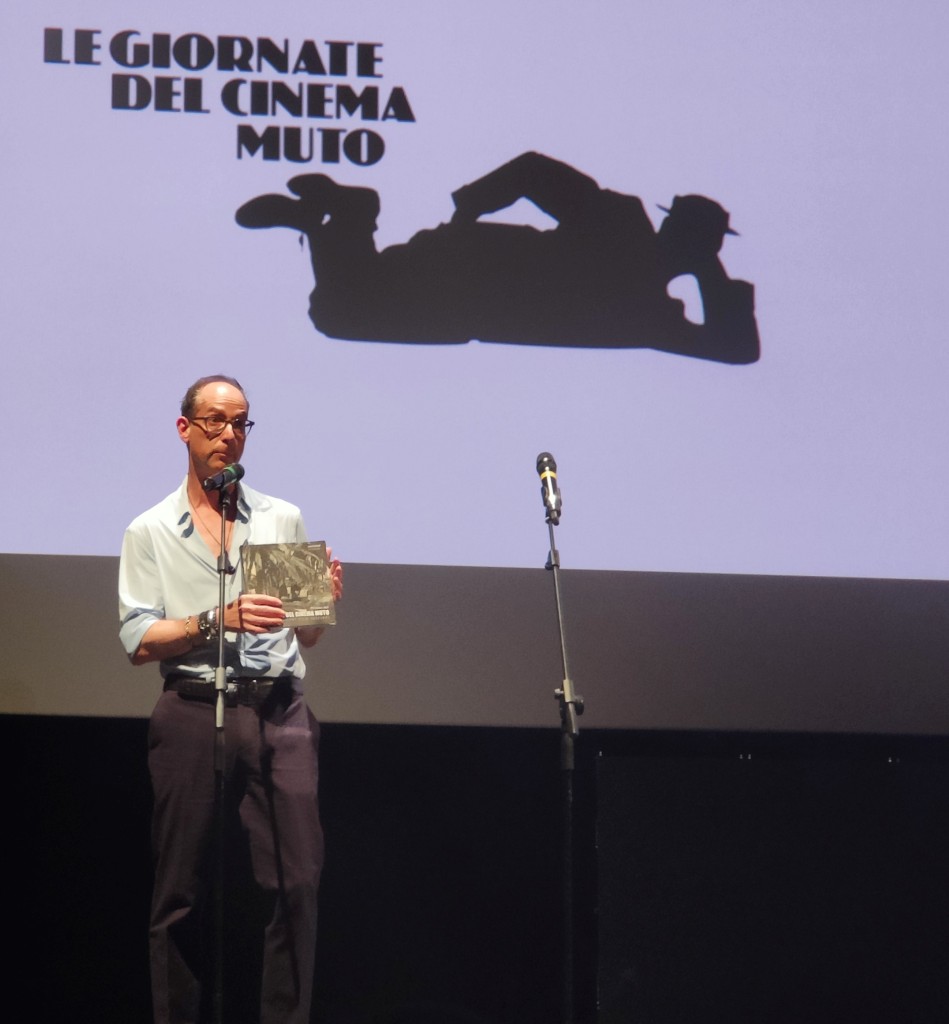

According to the Lonely Planet Visitor Guide, Pordenone in the northeast of Italy is “the kind of place you wouldn’t mind calling home”. For many hundreds of silent film enthusiasts, archivists, researchers, musicians, students, curators, authors and academics it absolutely is home… a place where one feels amongst family – part of a community brought together by a love for silent cinema. Each October, since 1982, these keepers of the flame have gathered in the town (apart from a few years camping out in nearby Sacile, during demolition and reconstruction on the festival venue) for le Giornate del Cinema Muto – acclaimed by Variety as the “gold standard for silent film presentation, complemented by the world’s finest musical accompanists”.

“The Only Woman Animator”: Bessie Mae Kelley and Women at the Dawn of the Animation Industry

Over the years, many traditions have grown up around the festival… the screening of the ident animation created by Richard Williams before selected evening events; the playing of Aaron Copland’s Fanfare for the Common Man at the Jean Mitry award ceremony (an accolade given to individuals and institutions who have distinguished themselves in the work of recovering and enhancing film heritage); and the greeting from the stage on Opening Night by the Festival Director: “Welcome home!”, which is always met with warm applause and perfectly fits that sense of returning to a place of belonging.

I’ve just returned to Scotland my from the Giornate and confess to feeling a wee bit exhausted. It’s been a whirlwind of screenings from 9am to midnight each day. People ‘do’ the festival in different ways. Some are completists who clock up ten hours a day in the cinema and can luxuriate in the confidence that they won’t have missed any surprise hits. I don’t have the stamina for 100% immersion. Instead, I have found a 5:2 diet approach (five films for every two espresso) is just about the right balance – skipping some screenings to recharge and catch up with fellow festival-goers. Five films for every two gelato works well for me too, especially salted pistachio! My chronic RAMO (Regret At Missing Out) the screening of Vendémiaire (dir. Louis Feuillade, 1918) with heroic accompaniment by Gabriel Thibaudeau and John Sweeney, who put in a shift each to cover the two-and-a-half-hour running time, is offset only because it meant I could linger over lunch with the lovely people from San Francisco Silent Film Festival (I blogged about my time there last year).

Here are my top five screening highlights picked from happy days of feasting on film (and ice-cream!)…

1. Steps in Time

I was caught completely off-guard by the pleasures offered by Ten Early Dance Films by Danish film Pioneer Peter Elfelt 1902 – 1906. This programme of shorts in the Early Cinema strand consisting of film recordings of ballet dancers at the Royal Theatre in Copenhagen was an absolute joy. They were programmed ahead of miscellaneous features, sometimes slightly randomly as far as I could tell… thus an enthusiastic Tarantella performed by two soloists was the appetiser for Tuesday night’s sober drama Pêcheur D’Islande, and the very jolly Jockey Dance featuring two prancing dancers dressed in jodhpurs and sporting horsewhips was on-screen ahead of the slow-paced Le Vertige (dir. Marcel L’Herbier, 1926). I have it on good authority that the dance films may have been transferred a frame or two per second too fast and so what would have been a gentle trot in the original choreography by August Bournonville was projected at a brisk canter… No matter – Stephen Horne managed to keep up the pace admirably!

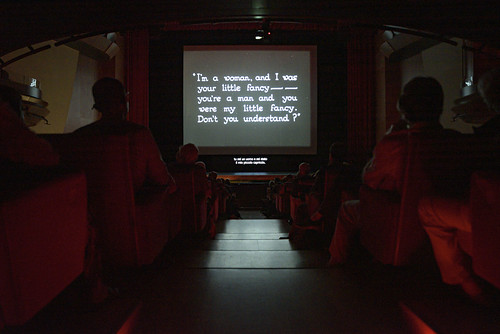

Best of all was Mavedanserinde or Belly Dancer – the extraordinarily fluid gyrations of an unnamed dancer in a nude-effect costume, wrapped around her torso like bandages (much more erotic than it sounds!). This saucy short was paired with the mid-week special event screening of Hindle Wakes (dir. Maurice Elvey, 1927) – a good match for this unapologetically sexual performance. Hindle Wakes of course is the excellent British silent drama in which the heroine Fanny Hawthorne explains her attitude to casual sex with the intertitle below…

You can read the HippFest programme notes from our 2019 Closing Night gala screening of Hindle Wakes at which Stephen Horne provided live accompaniment on piano, flute and accordion here.

2. “A drama from nature”

Der Berg Des Schicksals (dir. Arnold Fanck, 1928) was a welcome escape into the fresh air after the stuffy drawing rooms of a few films earlier in the week (Le Vertige I’m looking at you!). I loved this one! The catalogue indicates the US title was The Peak of Fate but I believe a literal translation would be ‘The Mountain of Destiny’. It is essentially the story of man (and woman) versus mountain – dubbed a “drama from nature” by Fanck. In the Dolomites, an expert climber is obsessed with his quest to bag the particularly tricky Guglia del Diavolo (or devil’s spire). His repeated attempts are thwarted by the complexity of the mountain’s pinnacle until one ‘fateful’ day he is finally defeated and falls to his death. Jump forward twenty years and his now grown-up son has inherited his father’s love of the mountains but has promised his mother faithfully that he will never attempt the Guglia. One day, the son’s childhood friend Hella makes her own attempt to conquer the mountain but a storm comes in and she is stranded on a precipice… Guess what! He renounces his oath and sets out to rescue her. This is a stunning piece of cinema – the mountain scenery looks sensational and there is a particularly beautiful sequence of clouds scudding across the peaks and beautifully lit cloud inversions. But what I want to impress upon you is that pretty much all the climbing is done ‘free’… as in without any ropes or safety equipment. They don’t even wear gloves for goodness sake! Emergency kit seems to have consisted of nothing more than sturdy socks and a pipe that our hero puffs on during the night they are stranded on the ledge.

If you’ve seen Free Solo (2018) or The Alpinist (2021) you’ll know what kind of sweaty-palm viewing I’m talking about, but this film was even more remarkable to me than either of those as it was shot without drones, instead using the presumably considerably clunkier cameras of a century earlier. The catalogue doesn’t make any mention of trick photography, but Fanck (director/editor/screenwriter/cameraman) was a free-climber himself and the person playing the adult son was a professional mountaineer so one can perhaps assume that they really were doing death-defying stuff. Another strand in the festival featured the films of Harry Piel, renowned for his stunt-work. But Harry jumping between moving vehicles and dangling off hot air balloons and windmills paled alongside these feats of derring-do. In conversations afterwards I was surprised to discover that some folk found Der Berg a bit boring – like a cinematic version of the children’s finger rhyme “down the hill and up the hill and down the hill and up the hill” but I was gripped from beginning to end. Big shout out to Mauro Colombis and Frank Bockius who took us to Alpine heights with their music and kept the tension throughout.

3. Frederick the Great

On the first day of the festival, the second programme of the day included The Love That Lives (dir. Robert G. Vignola, 1917). I confess I was not particularly eager to see this one as the plot summary, sketching out the story of a woman who sacrifices herself for the sake of her children and must then herself be punished, can get a bit tired (sigh). But it was only day one and I had had my coffee and gelato so dived in. I’m very glad I did. Pauline Frederick stars as Molly McGill, a mother whose brutish husband terrorises the children, gambles his wife’s meagre scrub-woman earnings, and gets himself killed in a brawl leaving her even worse off. Tragedy strikes when her young daughter is killed (audible gasp from the audience when we realise what’s coming) and Molly resolves the only way to secure her son’s future is to accept the advances of the businessman whose offices she cleans, on the understanding that he’ll help out financially. The arrangement goes sour when his unfounded jealousy becomes unbearable to her (go you Molly!), and she takes briefly to prostitution, before reasserting herself and returning to her cleaning job. Molly finds great solace in knowing that she has been able to provide a career opportunity for her son who is now a brave firefighter with a fiancée. Anyway, the main thing is Pauline Frederick is brilliant in the role – we believe in her and in every emotion that plays out on her care-worn face. Her gestures eloquently convey her situation but are never overplayed.

I have a terrible memory for faces and names and had misremembered Joan Crawford as the star of a Frederick film I had seen a few years before… and so it was only after The Love That Lives had finished that I realised Frederick starred in Smouldering Fires (dir. Clarence Brown, 1925) which was another of my highlights from the 2018 Giornate.

The Love That Lives doesn’t only rest on Frederick’s greatness… the children are naturalistic and sympathetic, the framing and lighting contribute wonderfully to the narrative subtlety, the fire scene at the end is very dramatic and the camerawork and editing belie the 1917 production year… just one year later than La Reina Joven (dir. Magin Muria, 1916) which screened earlier in the day and dragged along at a much less rewarding pace. Philip Carli on piano was fabulous and a total pro. He didn’t miss a beat when the house lights suddenly went up about ten minutes into the screening, nor a short while later when recorded music blasted randomly through the cinema sound system. The film concludes with an heroic act of Me Too sisterhood so it was rather frustrating that the concluding intertitle went something along the lines of “death reclaims the honour that she had sacrificed”. All that had gone before meant however that we were left with a profound respect for our heroine and the star who portrayed her.

4. Short cuts

I’m a big fan of early British shorts programmes such as The Great Victorian Picture Show curated by Bryony Dixon, Curator of Silent Film at the BFI National Archive. I got my fix this year with the one-hour programme of 19 Early British Films From the Filmoteca de Catalunya 1897 – 1909 whose discovery is described in Bryony’s programme note as being akin to unwrapping gifts at Christmas. This medley was indeed full of delightful treats – footage of an eccentric sea-faring electric railway tourist attraction on stilt like structures nicknamed “Daddy Long-Legs” (for which John Sweeney played a comically stately-paced rendition of Oh I do like to be beside the seaside), a playground gymnastic drill at an orphanage with a ‘cast’ of many dozens of orphans and choreography to rival Busby Berkeley, and a meditative phantom ride across the Firth of Forth from Dalmeny to Dunfermline shot in 1899 (yay Scotland!). Scotland also featured with shots of a circus parade passing through Inverness in the rain – which seemed a bit pointed when the previous short had been the same circus passing through Windsor Great Park in glorious sunshine. I’ll have you know that in all the 13 years of HippFest: Scotland’s first and only festival of silent cinema, it’s only ever rained once.

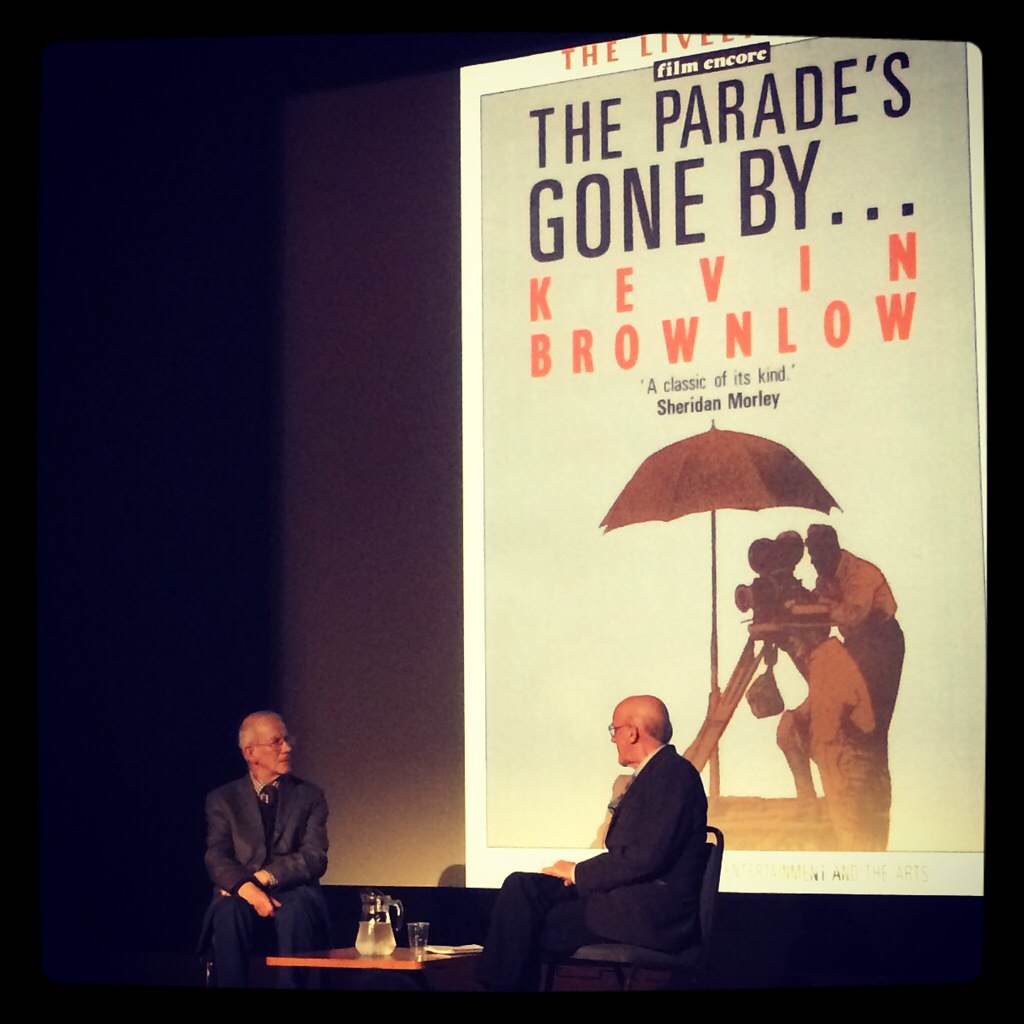

Pictured left: Kevin Brownlow, right: film historian David Bruce (former Director of the Scottish Film Council and the Edinburgh International Film Festival)

If I had to pick one favourite from the full Early British Films programme it would be Lace Making shot by Cecil Hepworth in 1908. A beautiful film record of old ladies with creased faces making lace as delicate as John’s piano accompaniment.

5. Not so silent night

I count myself supremely lucky to have been at the 2023 Giornate screening of Hell’s Heroes (dir. William Wyler, 1929). The director of celebrated films including Roman Holiday (1953) and Ben-Hur (1959) and the story itself, of three hard-bitten bandits in charge of a new-born orphan, will be familiar to many. I settled down for an enjoyable, cosy Western, confident of a good Sunday night’s entertainment.

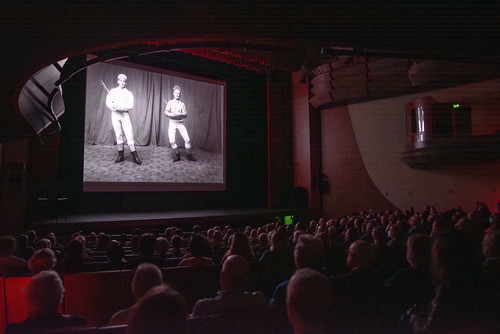

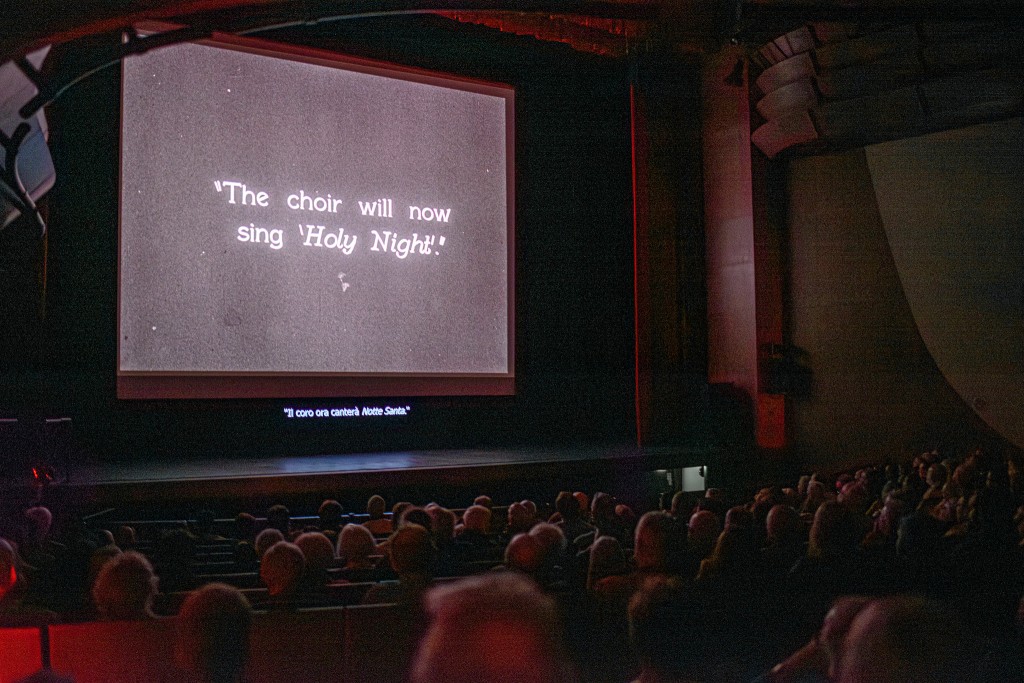

I wasn’t expecting the grittiness of the tale with the harshness of frontier-life emphasised by the starkness of the landscape. And I certainly wasn’t expecting John Sweeney to stop playing the piano and for the sound of a choir singing to start playing over the final scene. What struck me immediately was the quality of the Verdi’s sound system – so good that could make it sound like the music was coming from all around us, on all four tiers of the 900+ seat auditorium. Almost simultaneously I registered awe that the organisers had managed to find a recording of the carol that so perfectly fitted how one might imagine the voices of the congregation of ranch-hands and settlers’ portrayed on the screen. Then people seated at either end of each row of the theatre in the stalls and all the balconies stood up in unison, and it was only then that I realised that what we were hearing was an actual choir of singers. It was an incredible moment of live cinema and I was overwhelmed by its beauty. I am grateful that it was a surprise for me – I gather Pordenone had mounted a similar presentation 30 years previously, but I was completely unaware of that. John Sweeney hadn’t let the cat out of the bag either. When we spoke afterwards, he said simply he had been instructed: “just end in B flat” and that’s what he did.

Afew words about absent friends

At the Opening Night gala, Festival Director Jay Weissberg invited us to remember colleagues and friends who have died in the last year. “It is often traditional to have a minute’s silence at times like these” Jay said, “but let’s save that for the screen and instead make lots of noise for those we have lost.” And the packed Verdi theatre responded with cheers and clapping.

a whopping 336 pages this year. Worth the wait/weight!

The screening of The Love That Lives was dedicated to the memory of theatre historian David Mayer (1928 – 2023) whose research explored the links between stage and screen. The whole festival was dedicated to the memory of Russell Merritt (1941 – 2023) – a brilliant writer on film and a generous teacher. I had the pleasure of his company on an outing during the festival last year and he regaled me and our fellow day-trippers with absorbing anecdotes about Giornate gone by, Sherlock Holmes in silent film and much more. He was supportive of our own endeavours in silent film exhibition in Scotland and kindly allowed us to reproduce his programme notes for our screenings of Der Hund von Baskerville (dir. Richard Oswald, 1929) in 2019 for which restoration he had been the Associate Producer.

The Slapstick strand was dedicated to the memory of British film collector and historian David Wyatt (1948 – 2022). Many British people my generation will know David from his role alongside David Cleveland (founder of the East Anglian Film Archive) as ‘the Prof.’ in BBC’s Vision On series – conceived with emphasis on the visual to be accessible entertainment for Deaf children. Despite its segmented target audience, the show was universally loved. Loved for its weekly gallery of artwork sent in by viewers and presented by Tony Hart, an early version of the clay-mation Morph, and the silly slapstick white coat-wearing stop motion Prof. created by Cleveland and Wyatt. We remember David fondly at HippFest and the entertaining programme he presented for us in 2012 for the centenary of Mack Sennett’s Keystone Studios.

Three cheers for all the Giornate musicians

There are many musicians whose work I haven’t had space to mention but all the performances I heard were exceptional and I would just like to thank Neil Brand, Günther Buchwald, Meg Morley, Maud Nelissen, José María Serralde Ruiz, Donald Sosin, Gabriel Tibaudeau, Daan van den Hurk, Daphne Balvers, Lucio Degani, Francesco Ferrarini, Rombout Stoffers, Romano Todesco, Aaron van Oudenallen, Antonio Coppola, Juri Dal Dan, Ben Palmer and all the members of the orchestras for the magic you bring to every screening.

Brilliant and more comprehensive reviews have been shared by wonderful writers including daily blogs by Pamela Hutchinson at Silent London and by Paul Joyce.

You can read more about the festival, and all of the films, on the Giornate website